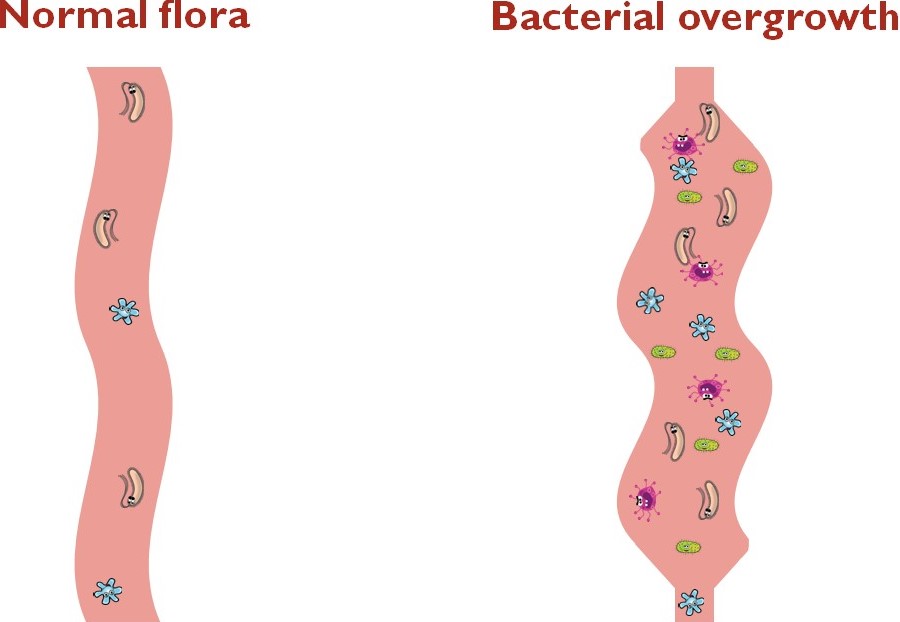

Everyone has bacteria in their intestines. The small intestine has a small number of bacteria, the large intestine has a large number of bacteria. They play an important role in supporting good health. They are important for forming poops, absorbing nutrients, making essential vitamins and helping the body fight some diseases.

The body uses different mechanisms to maintain a healthy intestinal flora. These include:

- A complicated series of muscle contractions moves food, waste and bacteria down from the stomach to the rectum, preventing bacteria from accumulating in the intestine.

- Stomach acid and bile kill many bacteria before they can reach the small intestine.

- A valve between the small and large intestines (the ileocecal valve or ICV) prevents bacteria from flowing backward from the large intestine into the small intestine.

In children with intestinal failure, one or more of these mechanisms is disrupted and too many bacteria sometimes grow in the small intestine. Symptoms of bacterial overgrowth can include abdominal distension (bloating), abdominal pain, gassiness, diarrhea, loss of appetite, poor weight gain and nutrient deficiencies.

Diagnosis

Bacterial overgrowth can sometimes be diagnosed using different tests. These tests can be invasive and are often difficult to interpret or to perform in children with IF. We may recommend starting treatment based on symptoms only and without specific testing.

Prevention and treatment

Antibiotics: The first treatment for bacterial overgrowth is usually low-dose antibiotics. They decrease the number of bacteria in the small intestine and help manage symptoms. Some children do well with one short course of antibiotics; others need to rotate multiple antibiotics over a long time. We will only recommend as much (or as little) antibiotics as your child needs.

Many parents worry that their child will become resistant to antibiotics that could be needed in the future. Antibiotics used for bacterial overgrowth are given in doses much lower than those needed to treat an infection. They act mainly on the bacteria in the small intestine and little antibiotic is absorbed.

Prokinetics: If impaired intestinal motility is contributing to bacterial overgrowth, prokinetics can sometimes help. These are medications that help the intestine contract better.

Surgery: When the small intestine is dilated, it cannot contract well enough to move food, waste and bacteria down to the rectum. If this is contributing to bacterial overgrowth and medications have not helped, we may recommend surgery to decrease the diameter of the small intestine.

Diet: While certain foods can make some symptoms worse, diet cannot prevent or treat bacterial overgrowth in children with IF. We may make recommendations to correct nutrient deficiencies made worse by bacterial overgrowth, if needed.

Probiotics

Probiotics are bacteria that help the body work well and so, are often called "good bacteria". They are naturally part of a healthy intestinal flora and help defend the body from infections caused by "bad bacteria".

Many parents ask if their child can use probiotics in addition to or instead of antibiotics. There is a lot of interest in using probiotics in children with IF. Unfortunately, probiotics are relatively new and we still do not know enough about them, including which type and how much to give. There may be benefits to using them, but there are also potential risks. If you are interested in giving probiotics to your child, discuss this with the CHIRP team.